Alive Studios recently had the privilege of being sent some wonderful 8mm cine film of Winston Churchill in the 1960s.

Our customer, British author Edward Gill explains what is on his film;

“I doubt if there are many now living who were in the House of Commons on the 27th July 1964 to witness Churchill’s last day in Parliament. Fortunate I was to be the very last person he passed by as he left the Chamber on that final day…”

The events of this historic occasion were caught on Mr Gill’s trusty 8mm cine camera. The 200ft reel of film has been transferred to various mediums over the years, including VHS and DVD, but only ever in standard definition. Keen to see what modern technology could do, he entrusted the film to Alive Studios to produce a High Definition scan, which they put onto a memory stick, which can be plugged straight into the USB port of a normal TV, and can also be watched and edited in any computer.

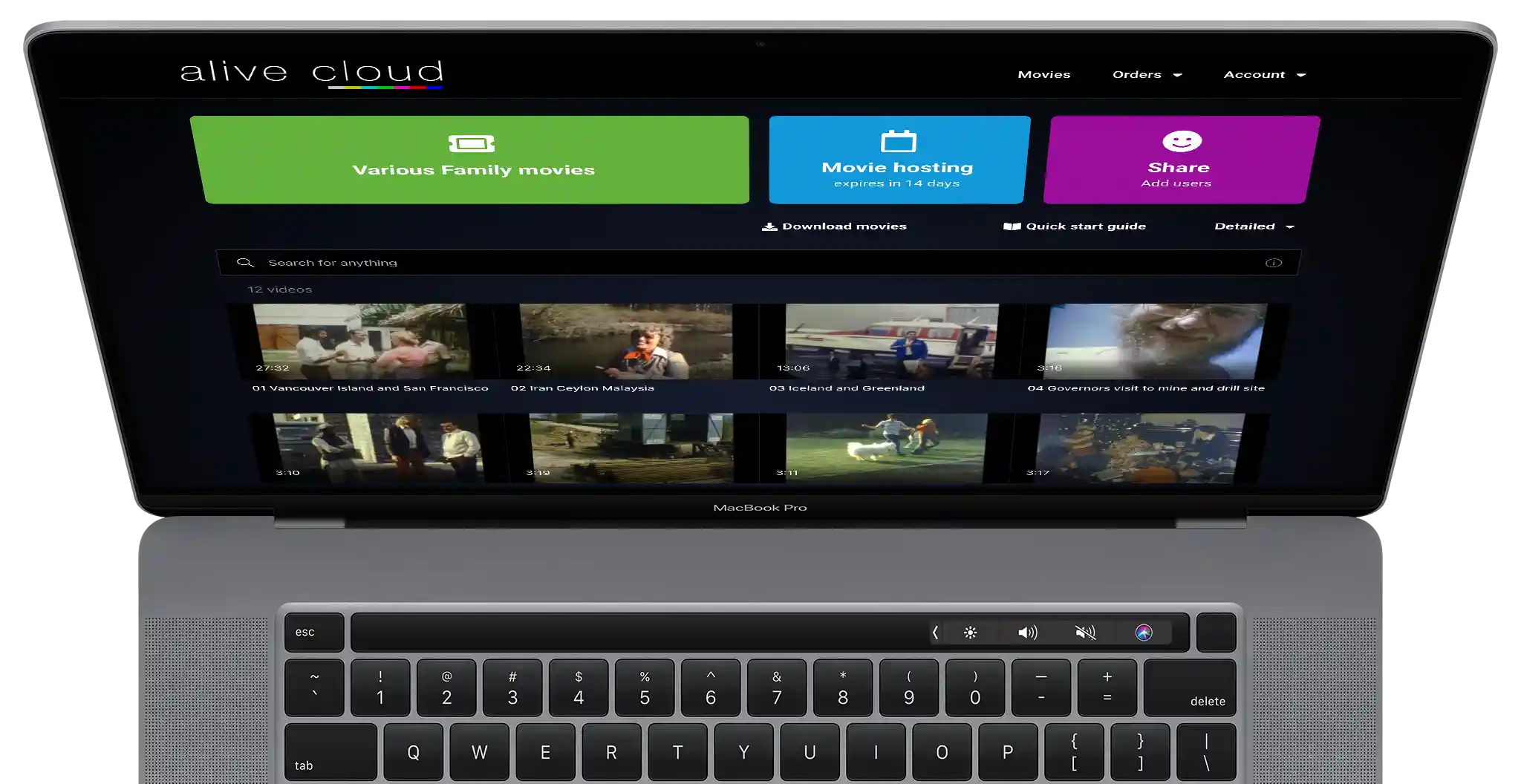

To enable Mr Gill to share this film with friends, family and other interested parties, Alive Studios also uploaded the movie in HD to their ‘Karishma Cloud’ which is an online gallery they give to all customers to help them safely share their memories online.

Incredibly, Mr Gill found the same event filmed from another angle on the British Pathe website, in which you can see Mr Gill filming with his cine camera!

Below is an excerpt from the book ‘Another World’, kindly reproduced here with permission from Edward Gill.

PART 1: Winston Churchill – The End of an Era

During the course of a long and eventful life, Sir Winston Churchill was, in equal measure, hailed as the saviour of civilisation and condemned as a man of war, ‘a warmonger!

In 1930, with all his soldiering behind him and his destiny still unknown, he wrote a small but important book dedicated “To A New Generation” entitled “My Early Life”; as only he could relate it. It tells of his birth at Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, of his father, the distinguished Tory politician Lord Randolph, and of his mother, the wealthy American beauty, Jenny Jerome; seemingly both had little time for their son.

He leaves his readers in no doubt that the two people who were the greatest influences on his young life were not his parents, but Mrs. Everest, his nanny and his heroic ancestor John Churchill, First Duke of Marlborough.

After a miserable school life at Harrow, young Winston went on to Sandhurst to pursue a career in the army. There followed adventures of heroic proportions in Cuba, India and the Middle East, culminating in the Battle of Omdurman where he took part in the last recorded cavalry charge.

He left the army in 1899, to pursue a career in journalism, and after a brief and unsuccessful adventure on the hustings in Oldham, left for South Africa as principal war correspondent of “The Morning Post’. The story of his capture by the Boers and his epic escape is legendary and need not be repeated here. Suffice it to say that it was all a preparation for what was to come – a long and distinguished career in Parliament. Years in the political wilderness between the first and second world wars provided the time for him to think, consult and write, and to ready himself for what lay ahead.

In 1930 he wrote his autobiographical gem – “My Early Life”, which brings me to the purpose of this preamble – to pass on a few words of Churchillian wisdom for the benefit of today’s politicians.

As I write, we are enmeshed in a quagmire of unfathomable complexity in the Middle East. Politicians, for I cannot call them Statesmen, of the twenty first century, too young to have experienced the horrors of war and seemingly with too little knowledge of history, are in danger of taking the world to a catastrophe with unforeseen consequences that even Churchill did not have to confront.

In a vain attempt to justify the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the American President quoted the words of his hero, Sir Winston Churchill. Unfortunately, neither his experience or wisdom matched that of his hero and through his Ambassador in London, I sent him the following quotation from Churchill’s “My Early Life”;

“Let us learn our lessons. Never, never, never believe any war will be smooth and easy, or that anyone who embarks on that strange voyage can measure the tides and hurricanes he will encounter. The Statesman who yields to war fever must realize that once the signal is given, he is no longer the master of policy but the slave of unforeseeable and uncontrollable events.”

Sadly, the President was supported by a British Prime Minister whose lack of experience and judgement was matched by his own. Neither had lived through anything like a world war or had any experience of military service. Not that I am suggesting these are necessary qualifications for ruling a country, but they are of enormous help if you plunge your country and perhaps the world into a boiling cauldron of war. History will be their judge.

By 1964, I was married and living in Surrey with my wife Valerie and Denise our infant daughter On the 27th July, the morning papers hinted that Sir Winston Churchill, now 89 and retiring at the end of this parliament, would today attend the House of Commons for the last time, It would be the end of lengthy and memorable political career that started sixty five years earlier, when he stood for parliament in the Lancashire cotton mill town of Oldham. In an age when many events are labelled “historic” only time can be the final judge; yet it is sometimes possible to recognise an event that will enter the annals of history, and this I thought was one I should witness.

Part 2:

Throughout a long and eventful life, monumental biographies of him have been written, and practically no part has gone unrecorded. I only wish here to add my own impressions of what I witnessed on that historic day.

To verify the accuracy of the newspaper speculation I telephoned Sir Winston’s London home from where a secretary confirmed what the papers were saying and advised me not to arrive at the House any later than half-past two. I arrived in the Central Lobby at two o’clock and wasted no time in completing a green card to request an interview with my friend Hugh Rees, the Conservative Member of Parliament for Swansea West. After handing in my card at the desk I took a seat beside the statue of Sir Stafford Northcote, 1st Earl of Iddesleigh whose descendents I had lived with for a short while in Shropshire during the war.

“Hats off strangers!” The voice of the policeman echoed through the lobby and I with everyone else stood silent and still to witness the Speaker’s solemn procession on its way to the House of Commons chamber. The procession passed and I resumed my seat. The lobby was full of M.Ps. and for a while I amused myself trying to decide from what they were wearing, which party each one belonged to. Most of the Tories wore black jackets and pin-striped trousers which was almost a sort of uniform. They contrasted sharply with the easily identifiable Labour Members’ drab suits, drab shirts and uninspiring ties which were clearly not of the club or old school.

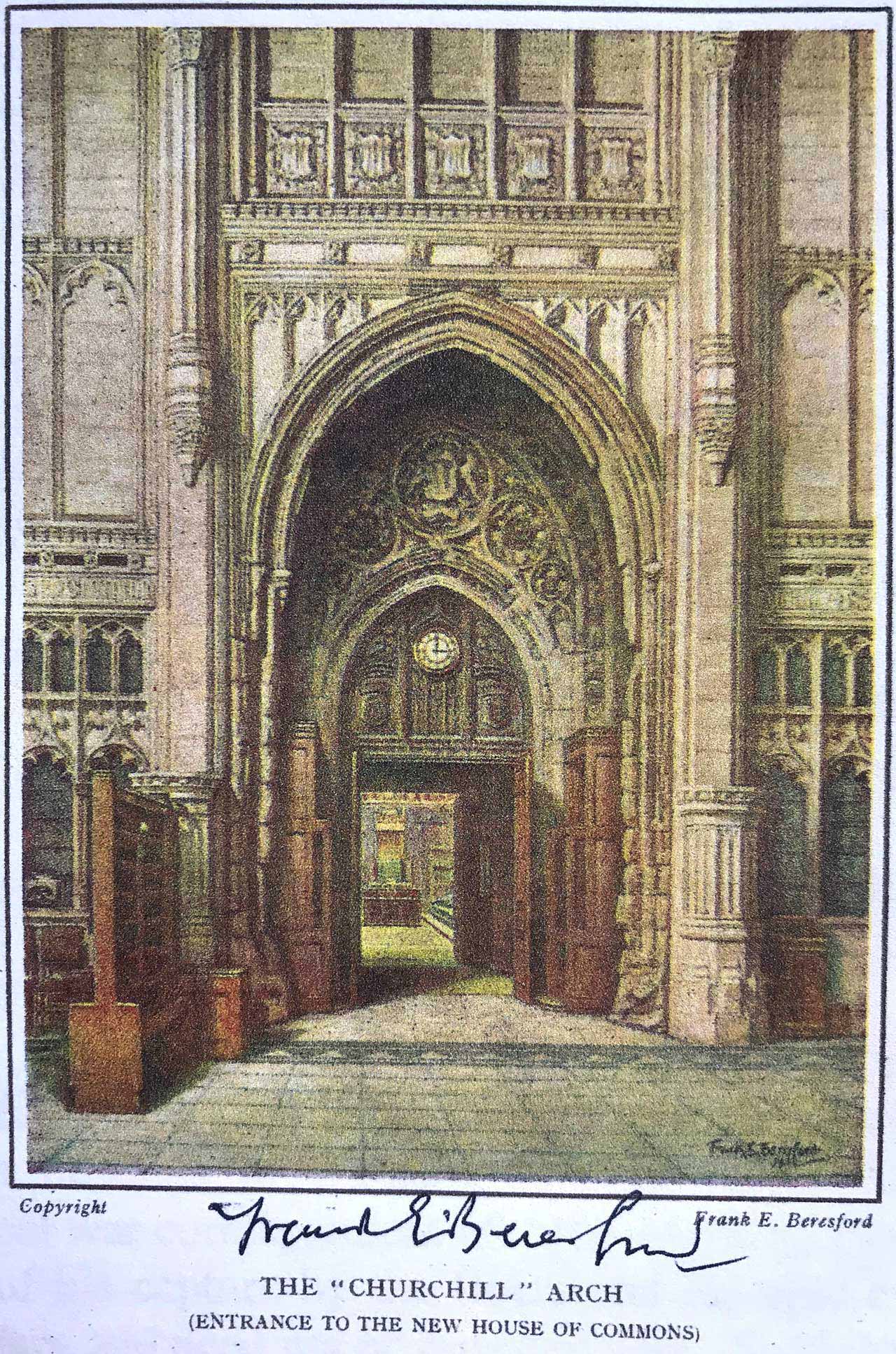

“Mr. Edward Gill” The voice of a policeman calling my name echoed around the lobby. I went to the desk and was given a ticket which read “Admit One to the Diplomatic Gallery.” What followed was beyond my wildest expectations. I was briskly ushered to the House of Commons chamber where M.P’s were gathered. Through the war scarred Churchill Arch, which is all that remains of the chamber bombed in the war, I could see the packed Government benches. There, sunk in the seat below the gangway, traditionally reserved for the most senior back-bencher and Father of the House, was the figure of Sir Winston Churchill, framed in the arch that now bears his name.

I doubt if there are many now living who were in the House of Commons on the 27th July 1964 to witness Churchill’s last day in Parliament. Fortunate I was to be the very last person he passed by as he left the Chamber on that final day and I have written about it in my book ‘Another World’

I went through the Churchill Arch and was shown to a private pew to the right near the Bar of the House. It was almost down at floor level directly opposite the Speaker’s Chair so I could not have been better placed.

Sir Winston was as ever, immaculately dressed in a black parliamentary suit with the long white cuffs of his shirt protruding from the sleeves of his jacket. He was wearing the familiar dark spotted bow tie, with a white handkerchief cascading from his breast pocket, and a gold watch chain hung like a garland across the front of his waistcoat. It was everyone’s vision of Churchill.

His eyes moved slowly around the chamber, occasionally catching sight of a friend or an old parliamentary foe. Perhaps in his mind he was re-living some memorable moments of battles fought long ago; of triumphs and what must have seemed at the time, less glorious moments of failure.

It was just after three o’clock when questions to the Prime Minister started. They followed the usual pattern and as they proceeded I could hear an audible murmur coming from Churchill, though I could not hear what he was saying, if indeed he was saying anything at all. Prime Minister’s Questions were followed by a statement from the Foreign Secretary who was about to leave for Moscow.

Sir Winston glanced at his Order Paper and decided it was time to leave. Here in the House of Commons, the final page of the long and distinguished parliamentary career of Churchill the Statesman was about to be written. Characteristically, the House appeared to ignore it, but there was in the air an awareness that all whose privilege it was to be present, were witnessing a unique moment in history.

Helped to his feet by two senior colleagues, each one supporting an arm, he moved slowly forward as his reluctant legs carried him along the green carpeted floor to the Bar of the House where, unhurried, he turned to face the Speaker and bow to the Chair to take his last leave of the House he had served for so many years. He was standing an arm’s length from where I was sitting and I can proudly claim that I was the last person he passed by as he finally left the Chamber.

Shortly after Sir Winston’s departure I decided to leave and go to his home at 28 Hyde Park Gate, where press reporters and cameramen were already waiting. With my small cine camera poised at the ready I managed to make my way to the front of the waiting media men who were jealously guarding their right to hold pride of place. While we were waiting, Lady Violet Bonham-Carter, one of Sir Winston’s oldest friends, came down the street and entered the house. She was closely followed by Lady Churchill.

A few minutes later a black limousine drove up to the house. The police cleared a space around the front door and Sir Winston was helped from the car. Heavily supported by two of his staff he just about managed to walk from the car and up the steps to the doorway. While he did so, I noticed that the press photographers refrained from taking their pictures until he was ready. Not at that time being privy to press protocol I knelt at his feet and proceeded to film this historic event. With a large cigar in his mouth, Sir Winston looked down and glared at me as though to say “What the hell do you think you are doing down there?” When the appetite of the press had been satisfied, Sir Winston was taken indoors and everyone left the scene.

Not until I got home did I realise the door of my camera film compartment was slightly ajar. I could not believe my bad luck; I had probably lost all my film. As a vital historical record, this film was important to me and I ‘phoned his house again on the

following day. “Is Sir Winston leaving for Chartwell today?” I enquired. “Yes, at about two o’clock” I was told. Determined to shoot the film again, I was outside the house well before the appointed time. His black limousine was waiting outside with the standard of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports fluttering on the bonnet.

Shortly after two o’clock the door of the house eased open and Sir Winston appeared on the steps. He was wearing a light grey suit with a grey homburg hat, and smoking a large cigar. Again I started to film as the great elder statesman was helped down the steps and into his car. I continued to film until his car left the cul-de-sac. Within a week my films were processed and to my surprise and delight both films were perfect. I had preserved on film a supreme moment of history.

Six months later Sir Winston was dead. He died on Sunday 24th January 1965. A few days later I again returned to Westminster and in bitter cold weather stood in a queue for over four hours to see him lying in state in Westminster Hall.

It is not the privilege of many to observe at close quarters the great men and women who have filled the pages of history. I sometimes envy those who lived through the times of historical giants such as Elizabeth I, Shakespeare, Cromwell, Handel, Wren, Nelson and Queen Victoria, during whose reign Churchill was born. But I count myself fortunate in having lived through the age of Winston Churchill and know generations as yet unborn who, to quote the words of William Shakespeare:

“Shall think themselves accursed they were not here” to witness this unique moment in our nation’s history.

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill

1874 – 1965

‘Blazoned in honour! For each generation

You kindled courage to stand and to stay;

You led our fathers to fight for the nation, Called “Follow up” and yourself showed the way.

We who were born in the calm after thunder

Cherish our freedom to think and to do;

If in our turn we forgetfully wonder,

Yet we’ll remember we owe it to you.’

Final verse of Harrow School song added for Sir Winston Churchill’s ninetieth birthday and first sung on 28th November 1964.

(this excerpt is copyright to Edward Gill and may not be duplicated or used without his express permission).